Life was not easy for my ancestors. We know that in the last years of the 17th century, when the available records start, most of them were humble peasants and craftsmen. Succeeding generations rose to leadership positions in diverse craft guilds or became traders. A number were Lutheran ministers or lay officers of the church, several others notable poets. Entering political battles for Slovak emancipation in the 19th and early 20th centuries, two of my forebears figure prominently in every textbook of Slovak history. A third became famous in inter-war Czechoslovakia for translating his ethical vision into business reality in a way that inspires even today.

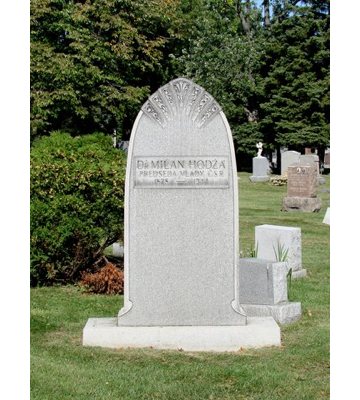

My mother’s father, Milan Hodža (1878-1944), was one of Slovakia’s and Czechoslovakia’s most prominent political leaders. He helped to create the new state of Czechoslovakia that was established after World War I (see History), to advance education and agriculture, and to foster Slovak economic and political strength. He served as the only ethnically Slovak prime minister of inter-war Czechoslovakia, holding office during the tense years of 1935 to 1938 as the stage was being set for World War II. Throughout his long political career, Grandfather Hodža propounded the concept of a federation of nations in Central Europe, a concept that forms part of the intellectual background for today’s European Union.

The life of my father’s father, Ján Pálka (1869-1935), was different but equally extraordinary. He was a businessman, not a statesman, but he too was moved by a vision. His contemplation of social and economic justice, derived both from his Lutheran Christianity and from a close study of socialist thinking, inspired him to completely restructure the management of the leather factory he owned and operated. Giving up sole proprietorship, he turned the factory into an enterprise that offered profit-sharing, shared governance, and many benefits for workers that were highly unusual at the time. This experiment, known as utopian socialism, was widely lauded in the Czechoslovkia of the 1920s. Through a mix of circumstances it failed and during the Great Depression the company finally went bankrupt, but my grandfather held steadfast to the rightness of his vision.

The Czechoslovakia in which my two grandfathers worked only came into being in 1918. Before that, Slovakia was a region within the Kingdom of Hungary (see History). During the nearly thousand years that Slovaks lived within a Hungarian state—and particularly from the end of the 18th century onward—they were confronted with increasing pressures to abandon their Slovak identity. In response, in the mid 19th century a powerful movement for the development and defense of Slovak national identity, culture, language, and ultimately political aspirations arose.

Among the most influential leaders of this movement, known as the Slovak National Awakening, was my great-granduncle Michal Miloslav Hodža (1811-1870). A Lutheran pastor, poet, and visionary, he made major contributions to the establishment of Slovak as a literary (not just spoken) language. He was also a major leader during the revolution of 1848, and helped frame the first calls for the political emancipation of Slovaks. Persecuted by government and church authorities during most of his active life, Hodža died in exile. In 1922, his remains were brought back to Slovak soil with great celebration.

The personal stories of a number of my ancestors–both humble and prominent–are interwoven with the story of the Slovak nation. Many of them are told in My Slovakia, My Family: One Family’s Role in the Birth of a Nation.